· Governance · 10 min read

From AI Pilot to Audit-Ready: How Regulated US and Canadian Teams Actually Ship Safe AI (Without Losing Their Minds)

Practical playbook for Canadian and US regulated teams to turn AI pilots into audit-ready, production systems by embedding governance, evidence, and monitoring from day one.

Across Canadian hospitals, banks, and public agencies, the story is familiar. A team builds a promising AI pilot, everyone is impressed in the demo, and then the project quietly stalls when it meets privacy, compliance, or audit review.

They are not alone. Industry analyses suggest that a very large majority of AI pilots never reach full production, often because organizations struggle to connect innovation with governance and risk management. (CIO)

For Canadian and US regulated teams, the bar is higher. You face:

- Health privacy regimes such as PHIPA in Ontario and HIPAA in the United States, which set strict rules for collection, use, and disclosure of personal health information

- Federal and state privacy frameworks such as PIPEDA in Canada and US laws and state privacy acts governing personal information

- Sector specific expectations from regulators such as Health Canada and the US FDA for machine learning enabled medical devices, OSFI for financial institutions, and guidance from privacy commissioners and US agencies on AI in the health sector (ipc.on.ca)

The result is a gap. Technically sound AI pilots sit in “demo land” because no one is confident they can withstand scrutiny from QA, RA, privacy, security, and internal audit.

This article offers a practical playbook to close that gap for Canadian regulated teams.

The Real Blockers Beyond the Technology

Most stalled pilots share a set of root causes.

1. Governance and risk are bolted on at the end

Pilots are often run inside innovation labs or data teams with minimal early input from QA, RA, privacy, or risk. Those stakeholders first see the system when it is “done,” at which point they flag fundamental issues: unclear purpose, missing consent, unclassified risk, or the possibility that the system itself is a regulated product (for example an ML enabled medical device). (fasken.com)

2. Evidence and traceability are missing

Auditors and regulators care less about the existence of an AI model and more about evidence: what data it used, how it was validated, what risks were considered, and who approved it. Without structured documentation, model inventory, and change history, teams cannot answer basic questions about provenance or performance.

Health Canada’s pre market guidance for machine learning enabled medical devices, together with the US FDA’s work on AI/ML-enabled devices, is explicit here. These regulators expect manufacturers to demonstrate safety and effectiveness across the lifecycle and introduce the idea of a Predetermined Change Control Plan (PCCP) to pre authorize certain model updates with clear evidence. (Canada)

3. Data residency and PHI create friction

Healthcare and public sector organizations are rightly cautious about moving data across borders or into opaque third party systems. PHIPA, for example, requires custodians to protect personal health information and to control its collection, use, and disclosure, often including audit logging for electronic systems. (crpo.ca)

Pilots that lean on generic public APIs or foreign regions can be non starters once privacy and security teams review the architecture.

4. No post deployment plan

In regulated environments, deployment is not the finish line. It is the beginning of ongoing accountability. Regulators and internal risk functions expect monitoring, drift detection, and the ability to respond if the model degrades or behaves unfairly. Frameworks such as the NIST AI Risk Management Framework, which centers on the functions Govern, Map, Measure, and Manage, reflect this lifecycle view. (NIST)

Without a clear plan for post market surveillance, leadership often refuses to move beyond experiments.

Key Concepts That Make Audit Readiness Concrete

Several concepts from emerging standards and guidance are especially useful for Canadian and US teams.

AI governance and AI management systems

AI governance means having defined roles, processes, and controls for how AI is designed, deployed, and monitored. ISO IEC 42001, the first international AI management system standard, provides a structured way to embed governance into the organization, similar to ISO management systems for quality or information security. (ISO)

Predetermined Change Control Plans (PCCPs)

PCCPs originated in the medical device context. Health Canada and the FDA now both describe PCCPs as mechanisms to pre authorize specific types of changes to AI enabled devices, such as retraining within defined boundaries, without requiring a brand new licence submission each time. (Canada)

Even outside regulated devices, the idea is powerful. It is essentially structured change control for models.

Model and data documentation

Model cards and data documentation summarize purpose, training data, performance, limitations, and appropriate use of a model or dataset. Health Canada’s MLMD guidance explicitly encourages model card like documentation as part of a submission package. (Canada)

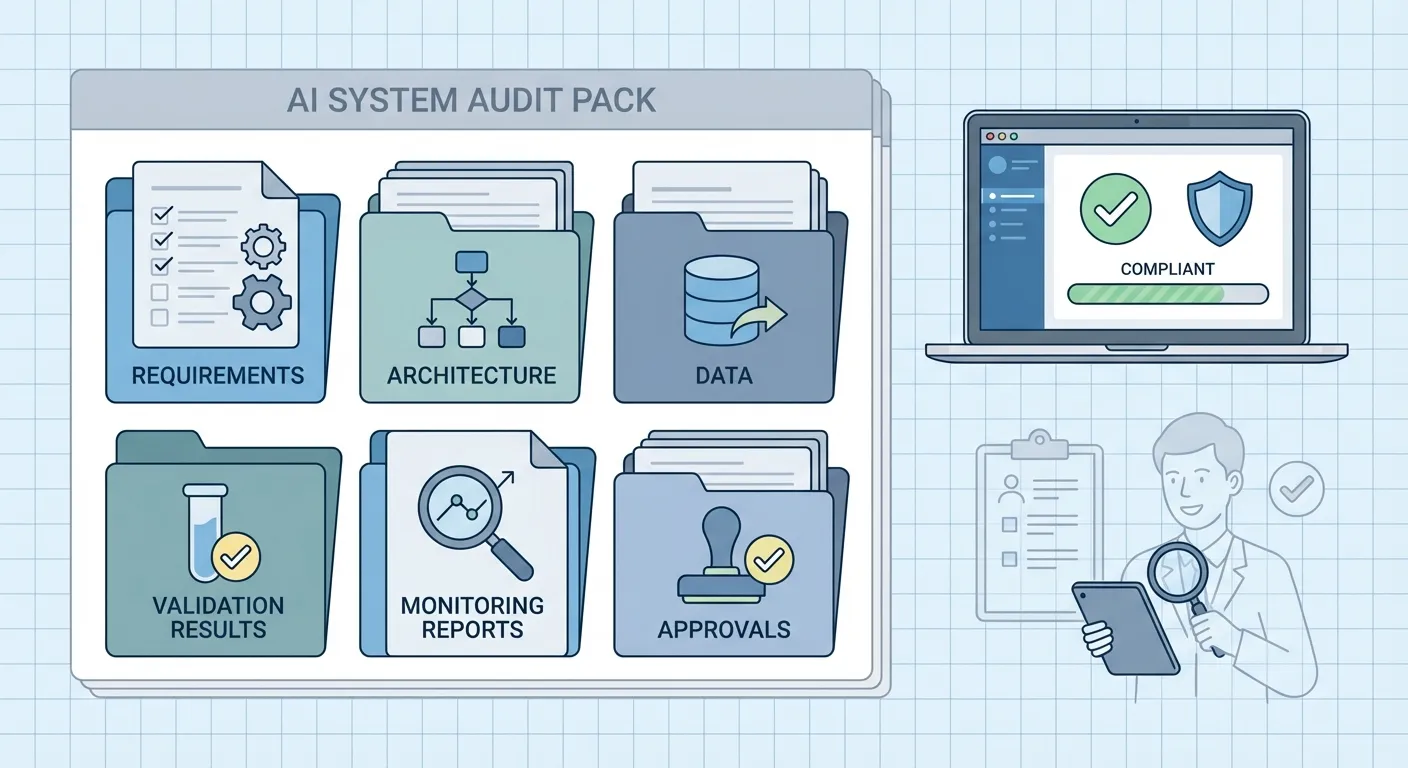

Audit packs and evidence bundles

An audit pack is a collected set of artefacts that tell the full story of an AI system: requirements, risk assessment, architecture, training and validation reports, model versions, monitoring results, and change records. The content will vary by sector, but the principle is the same. You do not want to assemble this in a panic the week before an audit.

A Five Step Playbook for Canadian Regulated Teams

This playbook is designed for a medium sized organization in healthcare, med tech, finance, or public service in Canada or the US. It is tool agnostic and focuses on the discipline, not a specific vendor.

Step 1: Involve risk and compliance at the idea stage

Before any data is pulled or a proof of concept is built, convene a short working session that includes:

- Business owner for the use case

- Data science or engineering lead

- Representative from privacy or legal

- Representative from QA or RA, or an internal risk or model validation function

- IT security and architecture

Use this session to answer three questions:

- What is the intended use, and who could be harmed if it goes wrong

- Which laws, regulations, or internal policies are in scope (for example PHIPA, PIPEDA, Health Canada MLMD guidance, OSFI expectations, public sector cloud and residency policies) (RegDesk)

- What categories of data will be used, and are any subject to additional constraints such as PHI or financial transaction data

Agree on a basic risk classification and on what evidence will be required to move from pilot to production. This avoids building a pilot that can never be approved.

Step 2: Treat documentation as part of development, not a final chore

From the first experiment, create a simple but structured documentation spine:

- A short design note that explains the problem, approach, and scope

- A living model card that is updated as the model evolves

- Versioned training and test datasets, or at least clear records of their origin and time window

- A log of key decisions and trade offs

Many of these artefacts can live in the same systems you already use, such as a wiki or repository. The key is consistency. By the end of the pilot, you should have enough material to assemble an audit pack without reverse engineering your own work.

Step 3: Build validation and guardrails into your MLOps

Validation for regulated use cases needs to go beyond a single accuracy metric.

At minimum, define in advance:

- Quantitative criteria for performance on relevant subgroups

- Stress tests for edge cases and failure modes

- Checks for bias and unfair impacts where applicable

- Security and robustness checks for adversarial or malformed input

Automate as much of this as possible in continuous integration or MLOps pipelines. Each candidate model version that passes validation should generate a short validation report that can be reviewed and attached to your audit pack.

NIST’s AI RMF can be helpful here. Its functions of Govern, Map, Measure, and Manage encourage teams to integrate risk assessment and measurement into the technical lifecycle instead of considering them as separate exercises. (NIST)

Step 4: Define a change control and PCCP like plan, even if you are not a device maker

Whether or not your system is a medical device, a PCCP style discipline is valuable.

For each AI system that leaves the pilot phase, define:

- Which parameters or components are allowed to change in routine updates, and under what triggers

- Which types of changes are considered significant and require additional approvals or even regulatory notification

- What validation must be performed before any change is promoted

- Who signs off on changes, and how approvals are recorded

Health Canada’s MLMD guidance and the US FDA’s PCCP documents provide concrete patterns for how to structure such plans in safety critical contexts. (Canada)

Adapting similar structure internally gives your governance and audit functions confidence that the model will not drift out of control.

Step 5: Operationalize monitoring and post deployment review

Finally, bake post deployment oversight into normal operations.

Set up:

- Monitoring of data drift and performance drift against your original validation benchmarks

- Alerts for unusual patterns, such as sudden shifts in input distributions or error rates

- Regular review meetings where model owners present monitoring results to a governance or risk committee

- A simple process to pause, roll back, or update the model if monitoring reveals issues

For healthcare and other safety critical domains, align this with existing post market surveillance processes. Health Canada and the US FDA already expect ongoing safety and effectiveness monitoring for ML enabled devices; similar principles can be applied to internal AI tools that affect patients or citizens. (Canada)

This continuous loop is where frameworks such as ISO IEC 42001 and the NIST AI RMF come together in practice. You are not just deploying models; you are running an AI management system that can show due diligence over time.

Two Short Scenarios

Hospital knowledge assistant

A large Ontario hospital wants an internal LLM assistant to answer staff questions about policies and clinical guidelines. Early scoping with the privacy officer confirms that PHIPA applies and that clinical data must not leave their environment. The team chooses an architecture that keeps PHI on premises and uses a retrieval layer restricted to de identified texts.

They maintain a model card that documents training data and limitations, and they build a small PCCP that describes how they will update the knowledge base as policies change. Monitoring tracks usage patterns and flags repeated low confidence answers for review. When surveyors and internal auditors ask about the tool, the hospital can present a neat evidence pack: risk assessment, architecture, model documentation, validation logs, and monitoring reports. The same pattern applies to US hospitals that must satisfy HIPAA, internal audit, and accreditation requirements.

GMP manufacturing quality model

A regulated pharma site in Canada or the US wants to use a predictive model to triage deviations and focus human review on likely critical cases. From the start, QA and validation join the project. Together they define acceptance criteria, test protocols, and a change control process that mirrors existing GMP expectations.

Every model iteration runs through a documented validation suite. A model inventory entry is kept current, and a governance committee reviews drift metrics quarterly. When a Health Canada or US FDA inspector asks how the AI fits into the quality system, the site can show not only the model’s performance but also how it is governed and monitored in line with broader quality management.

Turning Governance into an Advantage

For Canadian and US regulated teams, the choice is not between innovation and compliance. It is between unmanaged experiments that stall and structured AI programs that deliver value and withstand scrutiny.

Using a playbook like the one above, drawn from evolving regulatory guidance, AI management standards, and risk frameworks, you can move AI pilots from the lab into production with confidence. Health Canada’s MLMD guidance, the US FDA’s PCCP work, ISO IEC 42001, and the NIST AI RMF are not obstacles; they are templates for how to do this well in Canadian and US regulated contexts. (Canada)

If you are considering your next AI project, start by asking one simple question:

If this pilot works, what evidence would our auditors, regulators, and boards need in order to say yes to production

Design from that answer, not as an afterthought. Over time, this assurance driven mindset can become a differentiator for your organization, and for Canada as a whole, in building AI that is not only powerful but also trustworthy.

I will leave you with a prompt for reflection

What is the single biggest blocker keeping your AI pilots from becoming fully approved, audit ready systems today